The Philosophy of Paul Ricœur: Transmuting Pathos to Mythos in Psychotherapy

- Jack Dale

- Feb 21, 2023

- 8 min read

Paul Ricœur (1913–2005) was a distinguished French philosopher of the twentieth century whose work has been widely translated and discussed around the globe. He wrote extensively on a broad range of issues throughout his career, from interpretation, violence, suffering, ethics, and identity. Specifically, Paul Ricœur's theory of narrative identity and his framework for understanding suffering and distress in the context of narrative identity, offers an insightful perspective on the human experience. It highlights the importance of storytelling in constructing personal and collective identities, and the enduring search for deeper understanding that suffering provokes. Ricœur's work continues to influence contemporary philosophers and psychotherapists alike, and I hope this article provides a glimpse into the significance of his ideas.

A thread that ran throughout Ricœur's work is his hermeneutics of selfhood, fundamental to which is the need for one's life to be intelligible and bearable. In his seminal book "Time and Narrative," Ricoeur argued that narrative is a fundamental mode of human understanding and that our sense of selfhood and identity is inextricably linked to our ability to create and interpret stories. According to Ricoeur, the structure of a narrative involves a temporal sequence of events that are organized in a meaningful way to create a plot. This plot, in turn, provides a framework for understanding the characters and the events in the story, and it also helps to shape our interpretation of the narrative.

Ricoeur argues that the narrative structure provides a way for us to create a coherent and meaningful sense of self-identity. By telling stories about ourselves, we are able to construct a narrative that links together the various events and experiences of our lives into a coherent whole. This narrative identity is not a fixed or static thing, but rather it is constantly evolving as we encounter new experiences and events that challenge our existing self-conceptions. Thus, personal identity in every case can be considered in terms of a narrative identity: What story does a person tell about their life, or what story do others tell about it? Ultimately, Ricœur claims, narrative is the primary way we answer the question "who?" Who is this? Who said that? Who am I?

Ricœur contends that the response to the question who am I forms a chain "that is none other than the story chain. Telling a story is saying who did what and how, by spreading out in time the connection between these various viewpoints" (p.146). Ricoeur also emphasizes the importance of interpretation in the creation and maintenance of our narrative identities. He argues that our ability to interpret the events of our lives in light of our own personal narratives is essential to our sense of selfhood. In this sense, our narrative identity is not simply a passive reflection of our experiences, but it is an active and ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation. Here, the plotting of a story (or emplotment) is seen as an organising process that transforms the disruptive and unforeseen "reversals of fortune" (p.141), that threaten to destabilise one's identity, into the very history that constitutes selfhood. To truly answer who? one must tell an ongoing story. But what of those whose experiences are unspeakable?

A Story of Pathos

Throughout his life, Ricœur contemplated extensively on the nature of suffering and distress. In a paper entitled La Souffrance N'est Pas La Douleur (Suffering Is Not The Same As Pain), he (1992/2013) provides a framework on how one might understand suffering and distress in the context of narrative identity. He contends that "a life is nothing but the story of this life, and a quest of narration" (p. 30). Not merely a quest in the form of a journey, but a questioning kindled by suffering: "Indeed, questioning is related to plaints: Until when? Why me? Why my child?" (p. 30). Suffering invariably provokes an enduring search for deeper understanding, an attempt to grasp the meaning behind one's pathos.

Ricœur's early work explored the theories of psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers, particularly his views on suffering and boundary situations. For Jaspers, people encounter an existential boundary when they are "exposed uncompromisingly to their finality and to their inadequacy in the face of the factuality to which they are subject in existence" (Miron, 2012, p. 141). This existential boundary or limitation, Jaspers argues, is present to some degree in all forms of suffering: "Suffering is a restriction of existence, a partial destruction; behind all suffering looms the specter of death" (Jaspers & Grabau, 1971, p. 230). It is no coincidence that Ricœur's definition of suffering also shares a basic understanding with Jaspers. As Ricœur states,

Suffering is not defined solely by physical pain, nor even by mental pain, but by the reduction, even the destruction, of the capacity for acting, of being-able-to-act, experienced as a violation of self-integrity. (Ricœur, 1992, p.190).

For Ricœur, a human being is an "acting and suffering subject" (ibid, p.145), and despite encountering various violations that threaten the integrity of the self, a person will always try to find oneself again by actively telling and living their life story. "Thus", Ricoeur evocatively contends, "chance is transmuted into fate" (ibid, p.147). What is being articulated here is a process in which characters make sense of and organise the devastating and seemingly random calamities of existence by weaving them into a unique, temporalised narrative thread, a story told. However, if the suffering is too great, a person may become devastated by a surplus of painful feelings that cannot find a place within words or action.

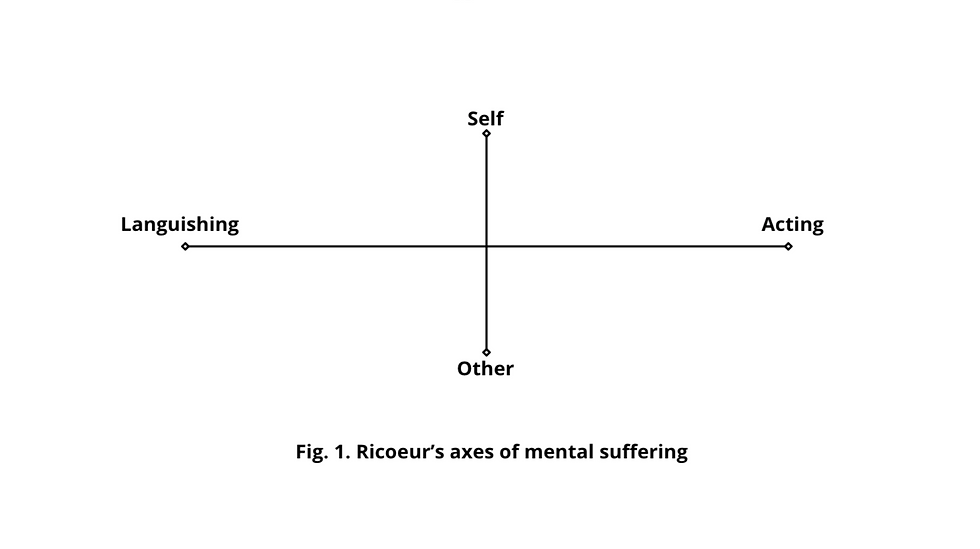

An important distinction Ricœur makes between somatic pain and mental pain is that while somatic pain typically manifests in a bodily way, "suffering is a mental experience that is related to the language-based reflections we make about ourselves and about others" (Vanheule, 2017, p.145). As such, Ricœur emphasises the need for sensitive tools to measure and assess subjective pathos, and consequently, he holds that suffering cannot be measured in the technical ways that somatic pain can, such as with X-Rays or CT scans. Rather, he maintains that we must read people's disturbances through "signs of suffering" (Ricœur, 1992/2013, p.30). To read and interpret these signs more effectively while simultaneously respecting the self-integrity and agency of the subject, Ricœur offers a conceptual model that discerns two orthogonal axes in which to situate mental suffering.

Ricœur conceptualises pathos in terms of the relationship between self and other and in terms of a continuum between languishing and acting. The self-other axis is drawn from Ricœur's foundations in phenomenology, in which the relationship between self and other is ontologically based: ""the self is not given to itself, but rather must be constituted as such, through the mediation of the other"" (Ricœur, 1992, p.6). On this axis, he suggests that suffering entails a withdrawal of the bond with the other. The suffering subject comes to feel isolated and overwhelmed by their pain, leading to a solipsistic nightmare in which "The world no longer comes across as liveable, but as emptied" (Ricœur 1992/2013, p.17).

In terms of the dimension between languishing and acting, Ricœur argues that pathos leads to an impasse at the level of agency or acting, acts explicitly that could transform one's self-experience. He describes four such acts:

First, suffering is often marked by impossibility at the level of speech. Here, one's suffering exceeds the capacity for words, and experience becomes unspeakable. When words fail, suffering manifests through non-verbal means, such as weeping, somatisation, eating disorders, or self-harm. When speech is possible, one can express forms of agency even on a minor level, which may lead to self-transformation. For instance, an appeal for help opens the possibility of dialogue, catalysing the integration of pain into a broader narrative.

Second, Ricœur situates the impossibility of acting at the level of general passivity. Sufferers may believe that nothing can be done about their situation, thus giving rise to a position in which they must endure the present state of agony. This may lead to feeling that they are caught in a vicious cycle, where nothing helps. When a subject realises that they can link concrete actions as potential solutions to experiences, a shift on this dimension occurs. For instance, when a person recognises that they feel less depressed on days they spend in nature, they observe a movement towards overcoming passivity despite their despair.

The third point in which Ricœur situates the impossibility of performing an act is in failing narration. Here, "suffering is expressed as a rupture in the narrative thread" (ibid, p. 22). What cannot be spoken cannot be weaved into a unifying totality. When pain cannot be placed within a narrative, it is atopic or without place. The effect of this is a chaotic "aporia" (Ricœur, 1992, p.155) in the centre of one's experience, and given Ricœur's equivalence of narrative and identity, a gap in narrative exists as a gap in selfhood.

The fourth and final point Ricœur refers to is the impossibility of valuing oneself. For Ricoeur, suffering leads to a breakdown in self-efficacy. Subjects become unsure if they can reliably trust their own opinions of their life and are unsure about what they actually want. Ultimately, this can lead to feelings of impotence, despair and shame.

Here, Ricœur's conceptualisation of suffering offers a valuable suggestion for those who work professionally with suffering, namely to be mindful of how suffering generates isolation from others, whilst also taking into account that suffering can be expressed through several agentic impasses: The inability to speak, take action, narrate, and value oneself.

Applications to Psychotherapy

One of Ricœur's (1992) most significant contentions for psychotherapists is that "understanding oneself comes down to being capable of telling stories about oneself that are both intelligible and acceptable" (p. 31). In a television interview with Jonathan Rée, Ricœur highlights how psychoanalysis attempts to understand those whose stories are unbearable and that result in the destruction of their own identity (Talking Liberties, 2020). In this sense, psychotherapy may be seen as a reconstructive process of both identity and narrative. Many contemporary theorists suggest that psychotherapy is a process that aims toward a higher organisation of mind for the patient (Guidano, 1987; Fonagy et al., 2002). Here, if we take seriously Ricœur's claim that it is “the identity of the story that makes the identity of the character" (p.148), increasing the coherence of the patient's narrative is comparable to cohering and organising the patient's identity, selfhood or mind.

For Ricœur, our experiences are not inherently organised; such organisation is configured through speaking about oneself and the world. In the experience of pathos, this organisation is missing or dispersed: "Suffering is expressed as a rupture in the narrative thread" (Ricœur 1992/2013, p. 22).

As is written about substantially elsewhere (e.g., Foucault, 1975; Vanheule, 2017), clinical models which attempt to understand suffering in technical ways are often limited in that they restrict a subject's ability to express their suffering via their own unique historical narrative. As such, they subordinate the subject to the discourse of the professional (i.e. "you have depression"), and hinder possibilities for narrative and organisational integration.

Consequently, the philosophy of Ricœur offers a contrasting conceptualisation of psychotherapy in which the therapist collaboratively assists the patient (from the Latin patientem "one who bears, suffers, endures”) to bear their unique story and give voice to what was previously unspeakable. Here, Ricœur's development of the emplotment of character provides considerable utility for the practice of psychotherapeutic case formulation. By plotting out the why and wherefore of the patient's suffering, clinician and patient collaboratively construct an integrative narrative that articulates the conditions, constellations, and dynamics that constitute both the negative and positive aspects of the patient's unique historical functioning, transmuting their pathos into mythos.

Here are some resources to learn more about the ideas of Paul Ricoeur:

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provides an overview of Paul Ricoeur's life and work, including his major contributions to philosophy, his key themes, and his intellectual influences. The article also provides a bibliography of Ricoeur's works, as well as a list of secondary sources.

The Philosophy of Paul Ricoeur - This book by Charles E. Reagan provides a comprehensive introduction to Ricoeur's philosophy, covering his major ideas, including his theories of interpretation, narrative identity, and the hermeneutics of the self.

The Partially Examined Life Podcast - https://partiallyexaminedlife.com/tag/paul-ricoeur/

Rick Roderick Lecture - The Masters of Suspicion - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4wetwETy4u0&ab_channel=ThePartiallyExaminedLife

Comments